What is your first association when you hear the word "Australia"?

Odds are nine out of ten that your first thought is that it's a place very far away. In fact, this notion about Australia is so pervasive and obvious that it doesn't let in any second association, when you hear the word "Australia".

In order to actually have room for any other thought about this continent, one must first get rid of that first impression, that Australia is a place very far away. However, getting rid of this thought is easier said than done, and the process often requires taking twenty-hour long plane rides. That's what we did, only, because neither of us is too comfortable with sitting down for twenty hours, we split the trip both on the way there and on the way back.

On the way to Australia, we made a stop both in Bangkok in Thailand and in Singapore. It's not actually necessary to make two stops, but we figured that we're not going to be returning to the far east any time soon, so we might as well see what's there. On the way back, we made a similar stop in Hong Kong, which is a place still adjusting to the fact that it belongs to China.

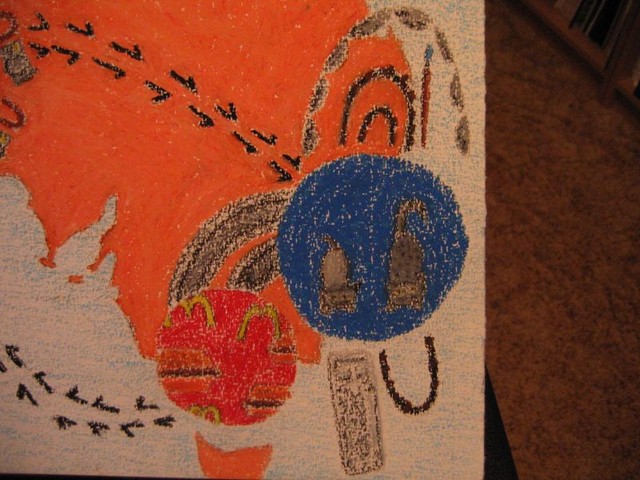

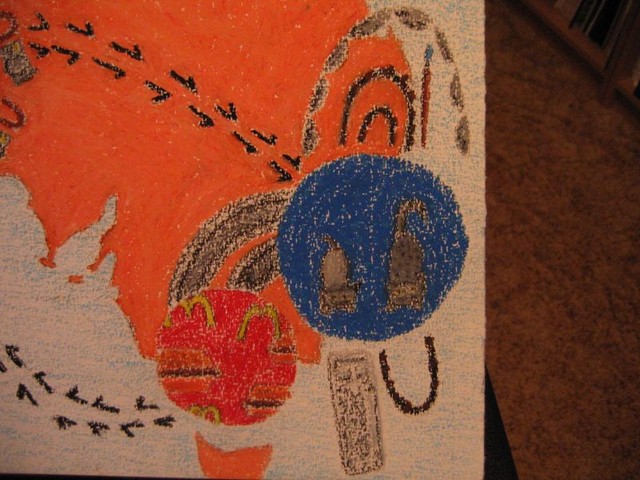

Between these, we managed to visit Australia for five weeks, and, believe me, when you get close up to it you do see things quite differently. Here is a sketch summarizing what we did in Australia in those five weeks. The original was given as a present to Na'ama and Barak.

What you see here requires some interpretation. It is a strange cross between your normal depiction of places and the written Aboriginal language that is used near the center of the continent (and has been in use longer than any other living written language on the planet).

First, regarding the style of the drawing. There are many tribes of Aborigines, living in many different parts of Australia, where different materials are abundant to make art/writing from. In central Australia, other than painting on caves, the ancient Aborigines used to draw on the desert's sand. Sometimes, while telling a story through the drawings, they would color it. However, you can't use brush-strokes when you're painting on sand. What they did, instead, was to drop globulets of paint on the engraved sand. This is why Aboriginal drawings are often entirely made of points of color and no brush strokes. We tried (cheaply, with crayons) to recreate this effect in our drawing.

Aboriginal drawing language is iconographic, meaning that every drawn bit is a symbol with a specific meaning, just as in everyday language, and not like in everyday drawings. The basic idea of this language is that "the earth records the tale". So, much of what is usually drawn are the footprints of animals, birds and insects, to signify their appearance. However, not all symbols are like that. This, for example, is the symbol for a pond:

Languages being what they are, sometimes variations in meaning cause one word (symbol) to become two, so that each variation has its own writing. This is the case with this symbol:

This, too, is a pond, but unlike the first pond, this is a pond where water can only be found in parts of the year. The other is wet year-round.

There are also symbols that signify things that are transient and that do not touch the ground at all. These two symbols, for example,

are for thunder (left) and lightning (right). Na'ama even told us of one Aboriginal artist who came to lecture for them at COFA, who said that in his drawings he often uses an Aboriginal symbol that means - at least as closely as there is an English translation - "Existentialism". So, you see, abstract concepts are also represented, and rather advanced ones too.

Now, the symbol that is usually the most prominent in Aboriginal art is that of the pond. The reason for this is that languages evolve by association, and the symbol for water pond, a very important feature in the Australian desert, also doubles as a synonym for "meeting place". So, in Aboriginal paintings usually most of the action centers around meeting places that have people gathered around them.

In our drawing, we decided to refrain from using the concentric circles symbol, but retained simple circles, instead, in which we depicted (in normal drawing mode) what each meeting place represents. For this we used colors. The colors are basically earth-tones (with some green and blue) as can be seen in original Aboriginal art, but in Aboriginal drawing language the colors do not signify anything. They are chosen purely for aesthetic reasons. Similarly, the positioning of occurrences along the fabric/wood/cave/ground means nothing regarding its position in map coordinates. Rather, these signify an aesthetic choice and a means to convey the mechanics of story-telling by letting your eyes follow the drawing.

Here we took, again, some European poetic license, and decided to make our drawing geographically correct. In the background, you see a map of the Australian continent, and the positioning of the three circles on it marks the real geographical positions where they are to be found.

Let us start from the first point, chronologically. This is depicted here

by the blue circle. This is Sydney. In the blue circle depicting Sydney, you will see the images of two cats: one small, colored a light gray and devilishly smart (smartness not depicted here) - that is Misty; the other as big as a common house-hold elephant and in similar colors - that is the sleepy Chat-Chat. They are the owners of a little house in a northern suburb of Sydney called Cremorne. They let two additional tenants share the space every now and then. Switching back to Aboriginal style, these are depicted above and below the blue circle.

A human being, in central-Australian Aboriginal symbols, is depicted in the shape of a letter U, with its opening directed towards the meeting-place. Why? Because the earth records the tale, and this is the shape left in the sand by a sitting human being after he gets up.

Na'ama is depicted as sitting above the blue circle. In Aboriginal drawings, men and women can be told apart, because near each person there is the drawing of what that person carries. Men have boomerangs drawn next to them, women have digging sticks and often also food bowls. We decided to extend this tradition by depicting Na'ama as a U shape next to which there is a paint brush. Barak, on the other hand, is drawn below Chat-Chat and Misty, with a large keyboard drawn beside him. To each his weapons of war...

Also, if you look at Na'ama's shape, you will see that there is a little U shape inside her large U shape. We thought that this would be a neat way to depict the fact that Na'ama is pregnant. A few days later, we came across an Aborigine and asked him what the proper way to depict a pregnant woman is, and he said that what we did was exactly right. After birth, the little U is painted next to the large U, together with all else that is being carried.

Surrounding Na'ama there is a large arch. This is an aboriginal symbol designating a cave, a shelter, and, yes, a home. By this we wanted to say that this is the home of the two cats and their pets. We now know that true Aboriginal writing would not have left Barak and the cats "out in the cold" while Na'ama is sheltered at home. Instead, the proper way to do this is to draw a second, upside-down arch around Barak, so that it almost touches the first arch. Maybe next time.

Off up and to the left of the blue circle, you see little shapes like arrows that point back towards the circle. In Aboriginal drawings there is no need to have special signs signifying what happened before what. If you see the footsteps of a person pass near a tree at one point and near a lake at another point, all you need to do is look at the direction that the footsteps are walking in order to see what happened first. Similarly, here it is very important to understand that the direction of motion is not, as you may have thought, towards the blue circle, in the direction of the arrows.

In fact, these are not arrows at all. "The earth records the tale" and these are footprints. In fact, this is the Aboriginal symbol for an emu,

so these are the footprints of the large Australian national bird, and it is going off to the left. In fact, this drawing is something of a metaphor. What we meant to depict here is the other large Australian national bird. Namely, Qantas

The Qantas bird took us to this place:

This is the bush. In the circle representing the bush you will see a drawing of the Uluru, undoubtedly the best known rock in the Australian outback. Our trip in the outback was a week long, and we traveled with a group. The group, of course, is depicted around the bush "meeting place". Again, we decided to creatively extend Aboriginal symbolism by adding a new symbol, like that used for "man" and "woman". This particular symbol, indicated by a man with a camera, is our symbol for "tourist".

This may all seem very silly to you, but you've got to believe me that when we showed sketches of this drawing to some of the people in the group, they were so excited by the fact that we actually drew them.

From the bush, south and to the east as the emu flies (metaphorically speaking), lies our next stop of the trip. This is the city of Melbourne and its whereabouts.

Here is the point to make a confession. As you may have understood from the fact that we showed drafts of this picture to members of the group, the plan for the drawing was laid-out long before we ever visited Melbourne. This had to be the case, because we nearly didn't complete this picture in time to give it to Barak and Na'ama, even though we started it in Alice Springs and worked on it as fast as we could.

For this reason, drawings from Melbourne on do not really depict what happened in our journey, but rather what we expected and planned. As it turns out, reality was quite a bit different.

Melbourne is shown with no people around and filled with McDonald's hamburgers. Both of these ideas proved to be wrong. First, we thought that we won't know anyone in Melbourne and will just travel there by ourselves. What really happened is that one of the people we met on the guided tour invited us to her house in Geelong (just outside Melbourne) and we traveled quite a bit together in the area.

Secondly, we imagined all these McDonald's hamburgers as a reaction to our previous experiences. In Sydney, Barak and Na'ama kept taking us to restaurants that were, by our standards, highly out of the ordinary. Some of these experiences (e.g. a Lebanese restaurant we ate in) were wonderful. Others, like a Chinese Yum-Cha place, were complete flops. Whenever we were left to our own devices, we somehow managed to find our way back to our favorite culinary experience: McDonald's. (See more about this in the Hong Kong section.)

The Yum-Cha place, especially, made a lasting mark on us. Yum-Cha is a place where the waiters run around with dozens of various Dim-Sam, and you just ask them to place one on your table every now and then. Specifically, we ate in a very "authentic" restaurant. (It was in the middle of Sydney's Chinatown, and most of the clientele were Oriental.) The only occasion in which we can recommend going to a Yum-Cha place is if you're really, truly, willing to not care what it is you are eating, and ignore any sign of what it really is, be that sign in the form of chicken legs sticking up on your plate, feathers, skin or otherwise.

In the end, however, we only visited fast-food restaurants once in our stay in Melbourne, and relied more on the local pubs and more "respectable" restaurants.

In retrospect, Melbourne should have been indicated by one of the Aboriginal symbols for weather. We were rather lucky in this city of "Excellent weather!" (see the Melbourne page for details), as most of the time there was no rain worse than a drizzle, but even that was enough to become uncomfortable.In Melbourne we rented a car, and all our travels from there on were driving adventures. This is symbolized in the drawing by having tire-tracks replace the old flying emu.

At the time of planning this drawing, we didn't know whether we were going to stop in Canberra, the nation's capital, or not. On the one hand, we heard that it was a nice garden-city. On the other hand, we feared it would be too cold, and heard a wall-to-wall consensus that there is nothing to see there. Our plan was to maybe just "pass by" Canberra, not making any real stop there.

For this reason, the tire tracks are shown grazing by the geographical location of the city of Canberra, but no "meeting place" is drawn there to symbolize the city. (This is somewhat ironic, because the name "Canberra" was derived from the aboriginal word "kamberra", literally meaning "meeting place".)

Nevertheless, we ultimately did make a stop in Canberra. We stayed there for three days, and I suggested we stay for a fourth, because there ended up being plenty to do there, and we didn't finish half of it. Orit, however, decided that we push on, and this proved to be the correct decision, as right after we left the temperatures dropped rapidly, roads were blocked and the city was trapped by snow such as was not seen there in the previous 28 years.

Continuing by car, we returned to Sydney, and from there started our way back home. Altogether, the 1000 or so kilometers from Melbourne to Sydney were completed with three places for sleep-over stops: Albury, Canberra and Batemans Bay. The detailed story of this drive, and especially pictures of the last stretch, from Batemans Bay to Sydney, have been given a page of their own.

After this drive we returned to Sydney, spent our last few days in Australia with Barak and Na'ama, and then headed home. Knowing our tastes now, Barak and Na'ama bid their farewells from us by inviting us to a steak restaurant called "The Oaks", where the food - as is quite common in Australia - is given to you in one of two forms: you can choose the "we cook" option, and get a steak, or the "you cook" option, and get fresh meat for you to grill on your own in the restaurant's grill. We, of course, chose the second option and loved every second of it, giving us a great last taste of the Australian continent and all the wonderful things that it has to offer.

|

|