The next morning we said goodbye to Bev and were on our way.

The trip was by now in its latter half, and we were beginning to feel the effects. Our first reflex was just to drive up to Sydney and do nothing else except be with Barak and Na'ama for the remainder of the trip. You can call our mood a "check-box" mentality, by which I mean that our thoughts ran something along the following lines:

Zoo? Saw one.

Safari? Saw one.

Desert? Saw one.

Winery? Saw one.

Etc., etc., etc.. It was like we couldn't make ourselves get into the car and driving, unless we knew that what awaited us at the end was something completely new to us, and not just "more of the same".

In the end, however, we decided to go south to Phillip Island, instead of northeast towards Sydney. Phillip Island boasts a great many different attractions (bird sanctuaries, a large family of seals, certain interesting rock formations such as "Pyramid Rock" pictured below

and other, similarly familiar things to see). However, nobody comes to Phillip Island to see any of these. People come there only for one reason. To see these creatures

in their natural habitat. That was something new to us.

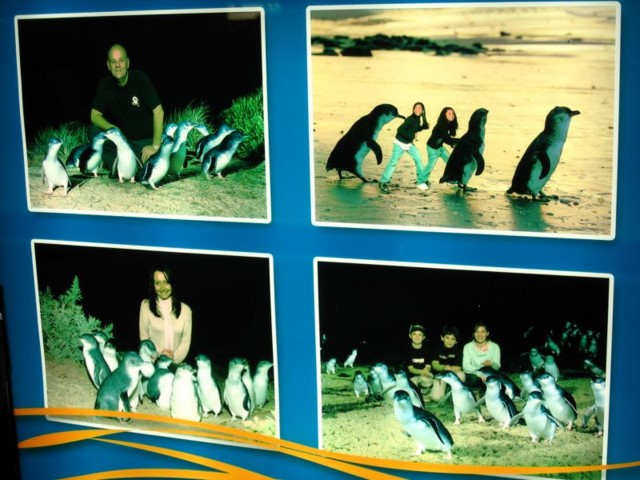

Sadly, nobody is allowed to take any pictures of them in their natural habitat, which is why tourists take their pictures by photo montage:

So, four hours of drive from Geelong took us to Phillip Island, in order to see Little Penguins, the smallest of all penguin sorts. Halfway there, the car's dashboard lit up with a new warning light we've never seen before:

We parked the car, looked in the instruction manual, and realized that the car is telling us that we were already on the road for two hours, and that we should take a break. The symbol meant that the car was inviting us for some coffee or tea.

Orit loved the idea. She kept saying: "Look! The car takes care of me! The car loves me! If it was up to you, we'd be driving all the way to Phillip Island now, but the wonderful car says that we should take a coffee break because it takes better care of me!"

The end effect, of course, was exactly the opposite of what the car manufacturers intended. In all later drives, Orit refused to make any stops of any sort, until two hours have passed and the warm-cup symbol lit up on our dashboard. She wanted to see that the car is taking good care of her...

By the time we reached Phillip Island, the weather has taken a turn for the worse. It was raining so badly one couldn't see from ten meters away, and driving was almost impossible. We didn't know if it was because of how far south we were, because of the season, because night had fallen and the temperatures dropped, or a combination of all of these, but it was bad. We thought we'll be the only ones crazy enough to look for Little Penguins in this weather.

In retrospect we know that the weather really was a little out of the ordinary. The next morning - and I'm getting ahead of myself here for a moment - we found the car covered in a two-centimeter thick layer of sleet, and the hotel owner told us he'd never seen anything like it. On the news that day we heard that there was heavy snowfall on the Great Ocean Road (thankfully, we missed it by twenty-four hours) and, more alarmingly, Canberra - our next destination - was experiencing the coldest day they have had in twenty years.

Still, returning to our night in Phillip Island, we didn't know any of these facts. All we knew is that the rain was bloody heavy, and we barely managed to find our way to the tourist information station, where they sold tickets to the night's show.

Flashback to the previous day: Orit was telling Bev how much different Australia is from the U.S.. She said to her: "Look at the apostles! Why, in the states, if there was anything like this, they'd have guys selling tickets to see it. Not in Australia, though. In Australia, anything that is naturally occurring - you don't take money for."

Well, I guess Phillip Island is not Australia, then. They had no problem offering us a view of the penguins for outrageous prices. If you wanted to see them closer up, the prices sky-rocketed even further. If it was any other day, we'd have just told them to forget it, but we traveled all this way through the pouring rain and there was nothing else to see. Plus, we wanted to see the penguins, so we bought tickets, put on our warmest clothes, and went to the shore.

So, what's the story with the penguins? It goes like this. The penguins swim out to the ocean, eating fish in the Tasmanian sea, all day. At night, they come back to sleep in their burrows on the shore, where they are relatively safe from their natural enemies. For this reason, as evening wears on, bands of penguins appear on the shore and try to make their way, past the seagulls, past the vegetation and the rocks, past the floodlights and the crowds, into their - by now artificially constructed - burrows.

The key thing to understand about these penguins is that they are extreme cowards. They will never venture on to shore by themselves. Instead, they will wait until a group of four or five gathers together, and then they'll run forward, all together, until reaching safety, hoping that in large groups the birds won't bother them. The birds, in fact, seem not to care about them either way, but when any one of the seagulls does step closer to the penguins, these dash back to the ocean in hysteria. In fact, it was not uncommon to see an entire group scared back to sea due to a seagull, while the penguin leading in front did not notice the threat at all and continued walking forward. It usually took that errant penguin a few moments to realize he was alone, at which point he would dart back into the ocean, even if he was only a few steps away from safety and had to run back down the entire beach in order to reach the ocean.

Several "notes to myself" in case I ever return to Phillip Island:

However, it was only when the number of penguins landing started dropping and we, cold and wet, decided to head back to the hotel, that we discovered the real secret of Phillip Island. We really should have caught the hint earlier, when we saw the groups of Japanese tourists head for home while the penguins were still at full assault. These same Japanese tourists, who took plenty of penguin pictures even though they weren't supposed to, knew something we didn't. On the way back we learned what:

It turns out that you don't need to pay for the premium seats in order to see the penguins up close. When you head up the ramp back towards your car, you realize that all the penguins are walking just to the right and left of the ramp, and you can see them walk on and on, while they are all the while within touching distance from you. (Though I wouldn't actually try touching them: penguins bite.)

We bid the penguins farewell, went to eat some late dinner in clothes with wet pant seats, then went to sleep.

The next morning, after cleaning the aforementioned sleet from our rental car, we started the long journey up north on the way to Canberra. The first leg of this journey was an exact backtrack that led us all they way back into Melbourne, leaving us with one final anecdote about the city.

We looked for some place to have a light lunch before heading out to the Hume highway, because I was afraid that the Hume highway was more or less 1000 kilometers with no place to eat. Orit thought I was unusually paranoid, but in retrospect had to admit that I was right. Australian highways are nothing like American highways.

Quite by accident, we saw a Nandos restaurant in Melbourne, and decided to hop in. The food was not very good, but what struck me about the place was the large map hanging over one wall. It was a map of the world, with red pins indicating where in the world there are Nandos restaurants. I don't know how up-to-date the information on the map was, but outside of the African continent there was roughly a total of a dozen pins. Almost all of these were located in the center of huge population complexes: In Australia there were only two branches: one in Sydney, one in Melbourne. In the U.S. the situation was similar: one in New York, one in Washington. The rest of the world? dido. There was only one exception. In Israel, there were two pins located very much near each other. One read "Herzlia", the other "Ramat Hasharon". You just gotta smile at that one.